Heart Surgeon's Impact on Medical Field

School of Medicine alumnus, H. Andrew Hansen, implants first Jarvik heart in Texas,

among other things.

By Kara Bishop

Photos by Felix Sanchez

In a cramped surgical debrief room at Lubbock’s Methodist Hospital, three doctors huddle in an ardent discussion. An hour before, a 65-year-old man had been rushed into the emergency room in cardiac arrest. Cardiologist Howard Hurd, MD, called in the cardiovascular surgeon, H. Andrew Hansen, MD, (Medicine ’75). They wheeled the man immediately into surgery for a coronary artery bypass. Now, lying in the intensive care unit, hooked to multiple IVs, a ventilator tube and an intra-aortic balloon pump, the patient still wasn’t responding. The heart team at the third busiest heart program in Texas needed to decide how to proceed — and quickly.

Hansen, Hurd and Guy Wells, MD, cardiologist and third doctor on the heart team, knew they were taking a risk. This would be the first implant in Texas of the Jarvik Acute Ventricular Assist Device (AVAD). They also knew it was the only chance they had to save the patient’s life.

The Jarvik AVAD, or Jarvik 7, named after its inventor, Robert Jarvik, MD, was the first successful artificial heart. A pump-style device with valves and a polyurethane bladder inside. Air pumps in and out of the bladder through tubes that are attached to an appliance — similar in size and appearance to a washing machine — powering the device to move up and down. When attached to the side of the heart, the up and down motion pushes blood through, giving the human organ time to rest and recuperate. Once rejuvenated, the human heart takes back over allowing the physicians to disconnect the patient from the Jarvik heart.

Twice in 1987, Methodist Hospital administration flew their entire heart team — doctors, nurses, staff members — to the Jarvik program’s training center in Salt Lake City, Utah, to learn about the Jarvik 7 and train on the procedure. At the time, the team was performing more than 1,200 heart surgeries a year, giving them special clearance from the Food and Drug Administration to work with this new technology. At the training center, Hansen executed the procedure twice in calves — the best model at the time for training on heart implantations. Every person on the heart team understood their role in the implantation procedure by the time they flew back home. Jarvik, himself, along with the head veterinarian and head engineer of the Jarvik program also flew to Lubbock once to visit the hospital and make sure everything was in order. The Methodist Hospital heart team was prepared to use the Jarvik 7 if needed. Turns out, their first case was just months away.

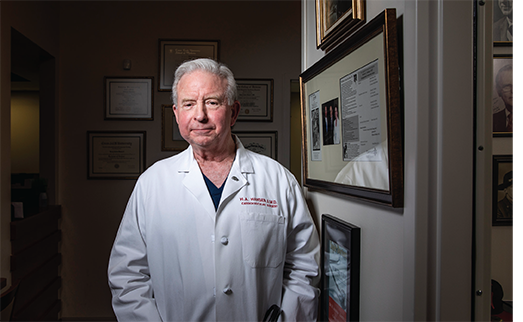

Hansen moved back to Lubbock in 1981 to join both Methodist and St. Mary’s heart programs after a four-year general surgery residency at Baylor College of Medicine and a two-year cardiovascular residency at Emory College of Medicine. Both schools had renowned heart programs, but working under Michael DeBakey, MD, — a world-renowned cardiovascular surgeon — at Baylor was a coveted position.

The innovations Hansen witnessed from working with DeBakey, in addition to a problem-solving personality inherited from his father, would motivate him to pursue the Jarvik 7 procedure full throttle. He’d spent his whole life waiting for this moment. A moment where he had the answer to the problem. The difference in this procedure and his training consisted of a human subject and, unlike the calf, this operation wouldn’t require three feet of breathing tube. The heart had the same number of chambers. And the heart is what mattered.

Hansen, Hurd and Wells agreed. This was the Jarvik 7 case. Hansen walks

down the hall to the operating room. “I’m ready. We’ve all trained for this to ensure

the safest method possible. This man is counting on me. The heart program is counting

on me.” Not only was this implantation the first in Texas, but less than 10 had been

performed worldwide.

The hallway seems endless, and for Hansen, that’s ok. It gives him time to mentally rehearse the procedure. Make the incision in the chest over the heart. Pull back breastbone and tissue. Clamp. Carefully insert the Jarvik 7 into the chest cavity and attach it to the left ventricle of the heart. Partially close chest. Connect tubing to the machine.

Two hours later and everything went exactly as expected — almost too easily. The patient lies peacefully on the exam table while the pump and device work in perfect harmony replacing the body’s most vital organ. The waiting game begins.

Hansen never actually planned to be in an operating room. As a young boy living in Port Arthur, Texas, he wanted to be an engineer like his dad. “Son, you don’t like to get your hands dirty,” his dad told him one day while they were discussing his future. “You need to be a body engineer.” Surgery wasn’t exactly clean, but doctors wore gloves and washed their hands often, so Hansen chose medicine.

He was one of those kids always asking “Why?” about everything to anyone who might have the answer. He had an unending curiosity for how things worked. And he loved a job well-done. When mowing his parents’ yard, Hansen would look back at those straight, clean-cut lines with a sense of satisfaction — feelings he would later experience after finishing a surgery. Neatly woven sutures marked the completion of a successful procedure that drastically improved a person’s life.

Of course, surgery meant medical school. Working toward his zoology degree as an undergrad at Texas A&M University, Hansen wanted to stay in his home state if he could, so his advisor told him to apply for every medical school in Texas. Hansen wasn’t afraid of trying something new, including this fledgling medical school in Lubbock, Texas.

Texas Tech University School of Medicine was the first school to accept him, so he moved north in summer 1972. After checking into the Rodeway Inn on Fourth Street and University Avenue, he noticed a dark red, angry sky. He’d just come from the coast and didn’t recall any hurricane warnings. Upon asking the manager, he got a knowing smile. “Oh, son, we’re about to have us a good old dust storm!” Hansen had officially been welcomed to Lubbock.

He settled into Drane Hall for the next three years — medical school in the beginning went year-round. His tenure at the School of Medicine was more of an apprenticeship, with first-year medical students scrubbing in to assist the attendings with surgeries. There weren’t manikins to practice on to perfect technique. There weren’t any residents assisting surgeons and educating students. Everyone was on the ground floor. The first surgery he witnessed in Lubbock was an aortofemoral bypass (joining abdominal aorta and femoral arteries) performed by Robert “Bob” Salem, MD. Hansen wasn’t a stranger to operations, having worked as a scrub tech during his undergrad, so he knew good surgery when he saw it. And he saw it in Lubbock. He wasn’t sure what to expect but was impressed by the speed and efficiency of the doctors. Quick, bam-bam-bam, vitals never dropping, nurses and staff never missing a beat while they assisted the surgeons. The recovery for the patient was as good as you could ask for.

Hansen juggled studying, lectures, surgeries and clinicals with “recreational breaks” that involved pickup softball and football games out on the dormitory front lawn. Even the professors often approachable on a first-name basis — though Hansen wasn’t comfortable with it — would join in. “Dr. Lutherer loved to get in there and play with us,” Hansen said. “He was pretty good!”

With the high-paced surgical aspect of his education, lectures didn’t generate as much excitement for Hansen, especially biochemistry. That’s what he thought, anyway, until he met biochemistry professor John Pelley, PhD. The founding faculty member, who still teaches in the School of Medicine Department of Medical Education, became his favorite teacher (and one, who, years later would flip through a binder in his office where he kept information about the first graduating class, see a photo, and exclaim, “Oh, hey! There’s Andy Hansen … an amazing heart surgeon.”)

Everything Pelley presented made complete sense to Hansen, and he appreciated the fact that there weren’t any curveballs on tests.

That wouldn’t be the case in the real world of medicine where curve balls were more common than not. Which is why Hansen sat bedside, eyes alternating between patient and machine, hoping the Jarvik 7 would do its job.

The three doctors took shifts keeping vigil over the patient. Nothing could go wrong. Adrenaline raced through Hansen’s body even off shift as he tried to relax in one of the empty hospital rooms, but his brain wouldn’t shut down: Did you do everything correctly? Was there anything you could have done better? Is the tubing attached correctly? What if he doesn’t make it? And then self-reassurance in the dark stillness: Yes of course I did — machine wouldn’t be working if I hadn’t. Did the alarm just go off? No, it’s working fine. It’s working fine. It’s working fine.

“We’re not going to quit on this,” Hurd said. It’d been a long, sleepless three days of observation so far.

“We should have done it sooner,” Hansen said. He was frustrated. They’d been timid and should’ve put the pump in immediately when they realized they were out of options. Instead, they hesitated. Only briefly, but would a few minutes have made all the difference?

All three men stared at the machine — willing the heart it was pumping to heal.

Hansen never thought about just how far the Jarvik 7 would catapult his career. In 2000, Hansen performed a minimally invasive abdominal aneurysm — another first in Lubbock — with the novelty prompting him to invite Karin McCay, the local NBC news affiliate health reporter, into the operating room to film and cover the operation.

“Yeah, in retrospect, that probably wasn’t the best idea,” he said. “Something could’ve gone wrong.” It didn’t, and the patient, a teacher from Clovis, New Mexico, was able to travel back home the next day — a recovery that was not common practice at the time.

McCay and Hansen met again in 2006. This time for the first heart surgery in the region using the da Vinci Robot, a procedure Hansen pioneered. He had followed the robotic technology progression for a decade and was thrilled to add it to his arsenal when it became safe and FDA approved.

“Star Wars technology is bringing Dr. Hansen a new surgical partner … da Vinci, a robot that can repair the beating heart, while the surgeon keeps his hands clean,” McCay reported. “If you’ve ever tried to hitch up a trailer, you know the hardest part is lining up the big gooseneck until it fits right over the ball in the back of the pickup and locks into place. It’s the same thing with the da Vinci robot, except you’re lining up three big goosenecks.”

When Hansen wasn’t reading everything he could on robotic surgery, he was researching varicose vein treatment. Back in his Baylor days under DeBakey, varicose vein surgery was what Hansen coined “barbaric.” The procedure was called “stripping.” With the patient under a general anesthetic, the surgeon made two incisions — one each in the ankle and groin — threading a wire through the groin incision and out the ankle, ripping out the vein. All the vein branches that were previously marked before the procedure would then be cut out with sizable incisions.

“Patients looked like they had been in a knife fight and had to stay in the hospital for days with their legs wrapped in cast-like bandages (Elastoplast). We didn’t even have good (compression) hose back then,” Hansen said.

Eventually, DeBakey refused to do the surgery, sending people home — no easy task, as some of them had traveled from other countries — telling them to “just wear support hose.” It bothered Hansen that medicine didn’t have a better solution.

In 2005, technology caught up to the science, making the varicose vein removal operation an outpatient procedure lasting 15 to 20 minutes, generally scheduled during the patient’s lunch hour, after which they would return to work.

Four years later, Hansen traded cardiovascular surgery for a full-time practice in vein disease. He had spent two decades taking chances, trailblazing, problem solving. , and it had taken its toll on him. He was ready to slow down, work regular hours. Still blazing trails, just in a different direction.

“I wanted to be there for my family,” said the father of five whose youngest will start college this fall at TTU — with plans to be a nurse. He’d spent most of their early years on call as an emergency heart surgeon.

“If we ever had the opportunity to attend an event or family outing, we had to take separate cars, because you never knew when Andy would be called into surgery,” his wife, Kathy Hansen, said.

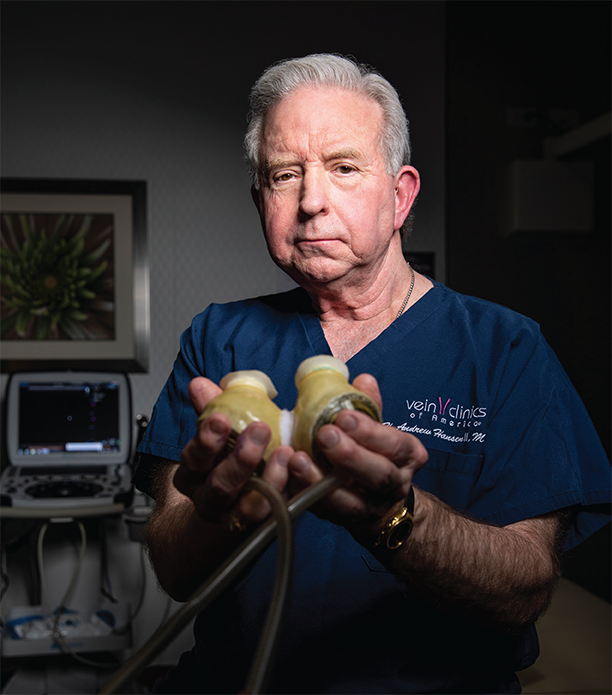

Hansen sits in his office at Vein Clinics of America in The Woodlands, thinking back on all the hills and valleys of an unending quest to figure out the “why” that defines his career. He’s taken stock of the cost of medical progress, of innovation, of advancement. It humbles him. And, perhaps that’s why, on a shelf in his office, he displays a model of the Jarvik 7 that teleports him back to that day.

Thirty-two years ago, the trio stood in the intensive care unit in Methodist Hospital. Four days had passed. No patient response. Time expired. The machine was past its capability. What would eventually become the “bridge to transplantation” had failed today in its limited form.

“I hate to lose,” Hansen says, defeated, as they unplugged the machine. Due to the novelty of the procedure and equipment, the FDA required pictures and removal of the Jarvik 7.

Scalpel in hand, Hansen prepares to open the patient’s chest for the third time in one week. He removes the implanted device that worked so hard to save the human equivalent while his colleagues help him document the Jarvik 7’s journey in Lubbock.

He had no way of knowing that the Jarvik 7 would eventually become the Jarvik 2000, a smaller device, powered by a battery, able to keep a patient alive until a transplant became available — a patient like the one on Hansen’s table.