Second-Year Medical Student Studies for Patients

Jennifer Lilley forces herself into isolation so that one day her elderly patients won't end their lives that way.

By Nancy M. Hood

Photos by Neal Hinkle

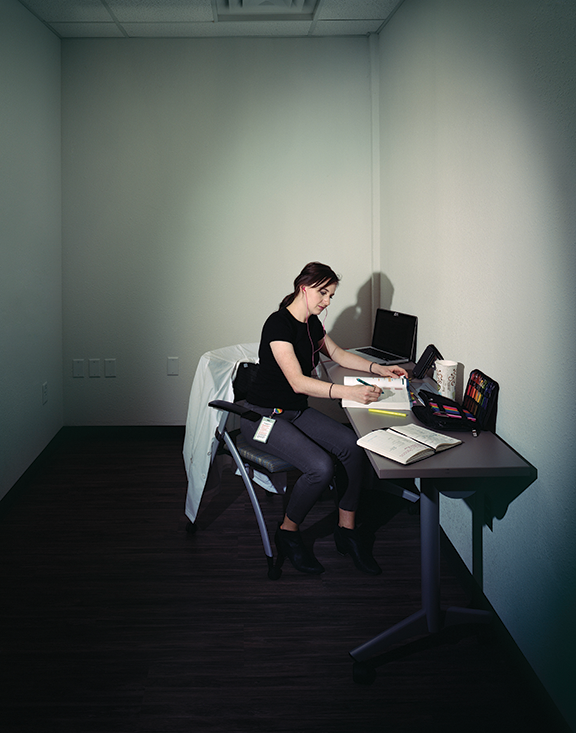

Sitting across from me, Jennifer Lilley looks out from under thick lashes with deep blue eyes and casts a wry grin as she talks about her first board exam — the first of three required by the United States Medical Licensing Board. All medical students take Step 1 Board exams at the end of their second year, after they complete the courses that comprise their classroom foundation in the medical sciences. After passing the exam, they can advance into clinical practice in local hospitals to learn the practical side of healing.

Although Lilley decided she wanted to be a doctor early in life, she committed to the decision because of the love she felt for her grandmother. Lilley was 24 when her grandmother died. Like so many seniors today, she spent her final years in relative isolation. Her health kept her confined to home, and she rarely left, even to run errands. She had no real social network. Lilley believes that her grandmother’s lack of stimulation, coupled with the isolation, accelerated her dementia.

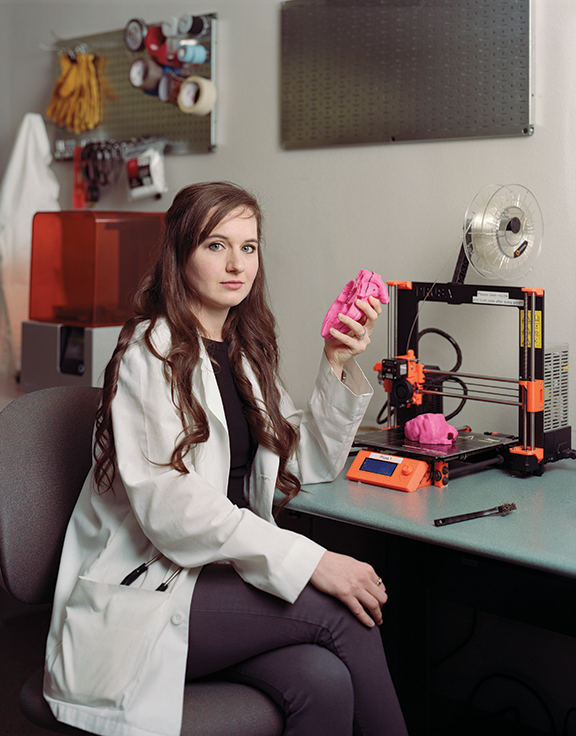

Read about the new 3D Printing Course.

As her grandmother’s health was declining, Lilley was working on her master’s degree in biochemistry. She was unable to spend the time with her grandmother that she would have liked, and that bothers her to this day.

“She died with my mom by her side in the hospital, but I couldn’t be there, and it is one of my biggest regrets.”

Lilley sits quietly for a minute, collecting her thoughts and sipping black coffee at a local Starbucks. Her experiences with her grandmother led to a first-hand view of how difficult end-of-life decisions and management can be for everyone supporting a loved one. She believes the health care profession will have to make significant changes to care for the largest over 60 population in U.S. history.

The senior population’s isolation has increased now that families are not as geographically close, and, due to technological convenience, it’s easier to shop online and have things delivered. Sometimes a doctor is the only person a single, aging adult might talk to or see in a week or a month, for some maybe even longer. This drives Lilley’s passion to give more time to the elderly.

“What if we approached caring for older people with the same compassion and time we spend with children?” asked Lilley. “I don’t know what it feels like to be in the last stage of my life, but I can imagine how frightening it must be. Every cough and ache has to be magnified, so maybe taking time to give a hug will make a difference.”

The few years between her grandmother’s death and the day she started medical school, gave Lilley time to think about the type of medicine she wants to practice — the kind of impact she wants to have on her patients. But first, in present day, she has to pass the exams.

The Conroe native checks her watch, already thinking about how many subjects she’ll have to review by days’ end in addition to her volunteer work. Always looking to step up her game, Lilley increases her medical knowledge by volunteering at The Free Clinic, providing care for patients without health insurance. Many of these patients further illustrate Lilley’s philosophy that people need to know someone cares.

“I had (an older) lady come in to the clinic a few days ago who wanted to talk about her diabetes. She already knew what she needed to do to improve her health,” said Lilley. “She just needed someone to talk to. She needed to feel safe for a few minutes and wanted a little human contact.”

Lilley checks her watch again, a signal that she really has to get back to her studies. She only has a few more days until the exam, and you can see the tension growing in her face as we talk. She has given as much time as she can afford right now. We stand and shake hands, but as she starts to walk away, she has another thought.

“You know, I think about my grandmother all the time. If she had been around people more, felt a little more affection and had something more to look forward to, she might have lived much longer. If that’s the thing I take into a medical career that helps me be a better doctor, then I suppose that’s a good thing to take away from losing her. I think she would be proud of that legacy.”